Welcome to episode 73 of the show.

Today we will deep dive into step one of the wealth creation system and wrap up our two part series on the topic. If you remember from part one of the series, the four steps in the system are to 1) identify your asymmetric advantage, 2) create surplus, 3) compound surplus, and to 4) repeat the process over again. This process is simple but key to creating wealth because it allows adherents to identify where they are, what they need to do next, and when they need to switch tactics.

Arguably, the most important step in the four-part system is identifying your asymmetric advantage. This is because knowing what your advantages and disadvantageous are will focus your efforts toward the areas of highest return. Contrast this with a one-size-fits-all approach to wealth creation that steers you toward tactics and tools that aren’t appropriate for you, even if they worked well for someone else.

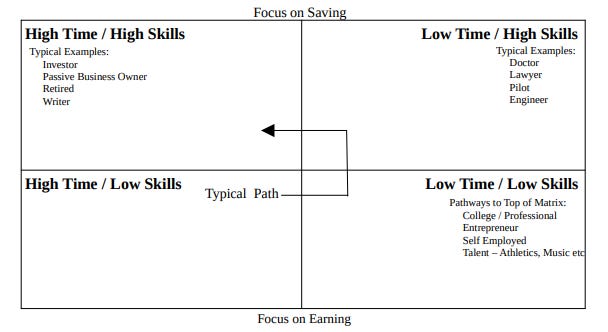

Let’s organize our thoughts on this topic in the following way. Picture a square that’s subdivided into four smaller squares such that we can label the bottom left, bottom right, top left and top right sections of the square with different names.

Getting back to our square composed of four sub squares let’s begin naming each of the squares based on specific attributes. The two attributes that we will measure in each of the four sub-squares are time and skills. Because we’re basing our model on these two terms it is worth defining them before we continue.

For our purposes, we define time as the amount of free time available on any given day. Clearly there is a great deal of subjectivity involved in determining how much free time you have but at the extremes it should be pretty clear. If you’re unemployed and single you have a lot of free time but if you’re a professional working 75 hours a week and have a large family, then you don’t. In between those two extremes you will have to make an honest judgment call as to how much free time you have available.

The next term is skills, and we will define skills in the broadest way possible. Skills, obviously includes the things we can do, but we will broaden the definition to include the things we know. In this sense, a carpenter and a philosophy professor both posses skills even though the professor would normally be said to have knowledge instead of skills. Stretching the definition of skills to its breaking point, I would also include your social connections and personal attributes inside of the skills criteria. The reasons behind this broad definition should become clear as we walk through our two-by-two matrix.

Now, let’s go through the matrix together beginning with the bottom left square, which is labeled “high time and low skills.” High time and low skills is where most young people find themselves at the beginning of their journey. It’s easy to think you’re in a disadvantaged position in this section of the matrix but in reality having an abundance of time available is a real asset and identifying your assets is exactly what the matrix is intended to help us do.

When you find yourself in either of the two squares marked low skills, you’re going to have to exchange your time and effort for capital through work. This is because increased earnings will be of greater advantage to you than any commensurate focus on savings could be.

Additionally, because every wealth-creation journey ultimately requires the acquisition of increased skills, you can’t remain in the low skills squares indefinitely. Remaining in the low skills squares would see you exchanging your greatest resource, time, for little return in the form of money. In other words, you would work to earn but be compensated very little because of the low value that the marketplace places on your limited skillset.

There are several paths you can take from the high time low skills square that lead to either of the two high skills squares including formal education, entrepreneurship, business ownership, investor and many others. Each of these paths has one thing in common, however, and that is that you must exchange your time for skills. Because you’re exchanging time, which you do have, for skills, that you don’t have, your journey will inevitably pass through the bottom right square of the matrix which is labeled “low time and low skill.”

The square is low time because unlike before where you had free time you’re now exchanging your time through work or study for increased skills. The square is low skill because, although you’re in the process of creating and growing your skills you haven’t attained a high skill level in any particular field yet. One advantage to this section of the matrix is that you can easily switch paths or reverse course if things don’t work out. If you don’t like the path that you’re on, then switch to something new and start over until you find a pathway that’s best suited to your circumstances.

The square that most people move to next is the top right square which is labeled “low time and high skill.” Picture a highly paid professional in this block of the matrix who has little time outside of their primary job. The advantage in this section is that, although time is limited, the person does have more income than their needs require. With high skills, they can go further by saving than they ever could have in the bottom half of the matrix which was marked by low skills and low earnings.

The top left square of the matrix is our forth and final section and it is labeled high skills and high time. Because this is more or less an end-state to your journey I won’t focus on it too much. The person in this section of the matrix has a great deal of flexibility to either exchange time for money or exchange money for more free time. They are also well positioned to increase their skillset further because they have the time to devote to new activities.

Having now run through the basics of each of the four squares in the matrix, let me go through them again using my own path as an example. I started out, as most do, in the bottom left of the matrix, in the high time and low skills section. I couldn’t make much headway focused on savings alone given that my earning power was limited, so I reoriented myself around skill acquisition. My path was typical, I went to college, developed skills, and increased my earning power and within a few years found myself in the upper right section of the matrix as a professional with low time and high skills.

Realizing that I wanted to move from low time and high skills to high time and high skills I identified that savings would have more impact on my financial future than increased earnings. This is because, as a working professional, my time was limited and my earnings were capped. You can only work so many hours, get so many raises, or climb up through the bureaucracy so fast before you hit a ceiling and this limitation on my free time and cap on my earnings led me to focus on savings. Essentially, I identified savings as my asymmetric advantage because I was in the low time high skills block of the matrix.

For over a decade my family owned just one car and I road a bike to work everyday. My family and I would forgo vacations in order to pay off debt and increase our investments. Other simple but effective strategies were piled up one on top of another until the net result was a single income family that saved about half of everything we earned. About a decade after implementing these strategies my family and I were able to migrate from the top right quadrant of low time and high skill to the top left quadrant of high time and high skill. Today, neither of us works and we’re able to pursue other interest and to, hopefully, continue to grow our skills.

Getting back to the point, the four square matrix forces you to identify where you are now and allows you to see where you should go next. Do you have more time than skills or more skills than time? How much thought have you given to what your actual skillsets are? Do you have unrecognized skills or opportunities that if pursued would maximize your return on effort?

A brief aside to clear up the term wealth might be helpful at this point. When most of us think of wealth, money is what comes to mind. Money, however, is just the most fungible form of wealth. Consider the fact that billionaire investor Charlie Munger claims he’d be happy to trade a few zeroes on his net worth for a little more youth. Munger’s comment is a powerful reminder that much of what we have has tremendous value even if it’s not easily measured in dollars. In fact, most of the time, wealth creation in the form of dollars is simply a transfer of some other, non-monetary form of wealth, into money.

A talented athlete converts their youthful athletic prowess into money over a number of years. They start out, in most cases, with lots of talent and no money and end up, hopefully, with reduced physical abilities and more money in old age. There is a sense in which the athlete was “wealthy” the whole time, they just fit the definition better after they’d converted their talent and abilities into money.

Hundreds of similar examples could be used to illustrate the point. Warren Buffett converted his intense focus and capital allocation talent into great wealth. Ed Thorpe converted his mathematical prowess and outside-the-box thinking into wealth by arbitraging options. Otto Bettman, used his knowledge of art and photography to smuggle trunks full of valuable photographs out of Nazi Germany. Once established in the United States he further leveraged his knowledge into a great fortune built around the budding photojournalism industry.

The point of these examples is that most people already have or will develop skills and advantages that can be converted into wealth. The two by two matrix detailed in this episode provides an entry point for you to consider where your asymmetric advantages might be. If you have high time and low skill then converting your time, a form of wealth, into assets by developing your skills will probably pay off best. If you’re a low time but high skill person, then you will benefit most from cutting expenses and capitalizing on your ability to earn more.

Remember that an asymmetric advantage is simply the idea of applying your greatest strength to an area where it will have the most impact. In hand to hand fighting, striking the softest part of your opponent with the hardest part of your body is an asymmetry. Wealth creation should follow the same logic and apply your greatest advantage to the area where it will have the most effect.

Revisiting our previous examples just imagine if Warren Buffett had attempted to build a fortune through athletics, or if Ed Thorpe had ignored his mathematical brilliance to pursue a career as the next great novelist. Or finally if Otto Bettman had pursued an acting career instead of applying his knowledge of art and photography to the problem of smuggling wealth out of Nazi Germany. The examples may seem silly in others but how often do we settle into careers ourselves that are ill-suited to our abilities and temperament and yet still wonder why we’re not getting ahead?

In addition to the two by two matrix already described in this episode, a Venn diagram of your interests, talents, and opportunities can help you identify your asymmetric advantage. Starting off with your interests, it’s difficult to overstate just how far being interested in what you do can take you. Few fortunes were built by people who hated every minute of what they did. To be sure, all pursuits have their frustrations, but having passion behind you can be an immense tailwind on your journey.

In my own case, I spent decades interested in investing and could pour myself into the subject for hours on end and yet I worked in an unrelated career field. The career I pursued was interesting and rewarding in its own way, but I realized after stepping away from it that I’d been forcing myself to enjoy it for years, years that could have passed by more enjoyably if I’d made my passion my work from the beginning. Life is too short to devote years and years to tedious pursuits in the hopes they will one day fund your real interests.

Talents are another key to finding your asymmetric advantage. Do people routinely tell you that you’re good at something or that certain things come naturally to you? There is an old saying in investing that goes, “don’t fight the fed” but in my opinion a similar “don’t fight your talents” sentiment could be applied to your life.

Again, in my own case, certain activities come easily to me and others do not. When it comes to physical fitness I can easily climb a rope or crank out pull-ups with minimal training but if I do two or three somersaults in a row I nearly throw up from motion sickness. How crazy would it be for my motion sick self to pursue a career in gymnastics or ice skating? Again, I’m sure we all have similar stories about what comes easily to us and what does not and we shouldn’t ignore those innate attributes.

Mohnish Pabrai, tells a story from his undergraduate days when he took an elective business class and effortlessly aced it. The professor urged him to switch majors from engineering to business but Mohnish refused. He had drawn the wrong conclusion, figuring that if the class was that easy for him it must be full of idiots. Committed to this line of thinking he doubled down on his engineering studies, considering himself virtuous for having taken the difficult path. Decades later, as a successful investor and fund manger, he could see that he’d ignored his natural talents and spent years in an ill-suited career field. He realized that the business school route wouldn’t have been the “easy way out” but would, on the contrary, have capitalized on his asymmetric advantage.

Finally, opportunities should also be included in your Venn diagram. Do you have a family member who’s successful and willing to take you under their wing? Do you live in a location that offers up unique opportunities? Is there something in your life that others would consider a massive windfall that you yourself overlook because you’ve grown blind to it?

When my family and I lived in Italy my kids were able to participate in a local cycling club. Every small town in the area had one and any kid who wanted to could participate free of cost. The club provided the kids with a bike, coaching, and all the necessary equipment to help them grow their skills and knowledge of the sport.

Now, to the Italian kids this training opportunity was no big deal, just part of life, but think of the advantage they had over a kid in small town Texas who also wanted to race bicycles. The Texas kid would have to buy his own equipment and would probably need to travel a considerable distance just to get equivalent training, if equivalent training could even be found. The opportunities for aspiring cyclists in Texas are no where near the opportunities available to kids in say, football. I highlight this example just to illustrate how many opportunities life offers up to us and to show how many of those opportunities go unnoticed.

Summarizing the concepts we’ve covered so far leads us to the following key points. First, your asymmetric advantage is unique to you. It could be a skill, something you know, someone in your network, where you live, a physical attribute or any number of other things.

Next, evaluating where you are on the two by two matrix will point you toward your specific asymmetry. It will force you to ask the following types of questions. How much free time do I have and what skills do I posses? Should I focus on efficiency and saving or increasing my earning power? Will I pursue skill acquisition through formal education and training or entrepreneurial ventures? Again, the two-by-two matrix should give you a starting point and a direction that will begin to answer those questions.

Next, performing a deep dive into your own talents, opportunities, and interests using a Venn diagram will further guide you toward your asymmetric advantage. The Venn diagram should begin where the two-by-two matrix left off and move you closer to identifying your specific advantages.

The final step of the wealth creation system prompts us to repeat the process over again. This reminds us that life is a constant process of observing, orienting, deciding and acting and that there will always be detours and dead ends along the way. The detours and dead ends are nothing more than temporary setbacks so long as we don’t stop progressing. As long as we go through the four step system regularly then we won’t stagnate and we will ultimately get where we want to go.

With that we hope you enjoyed the show and if you’d like to support us there is no better way than to sign up to our Substack or listen to us on Fountain where you can exchange value for value. As always, we will be back again next week with another investment focused write up having wrapped up our two-part series on the Wealth Creation System.

Thanks for listening and we’ll see you next week!

SUBSTACK-ONLY BONUS

Below are a couple of the top podcasts we enjoyed over the past week!