Welcome to Episode 101 of Special Situation Investing.

A business that earns a high return on capital, can be purchased at a reasonable price, and that has a strong protective moat, is the holy grail of investing. An investment that scores highly on all three criteria should, if found, make up a large percentage of your portfolio. Determining how much of your money should go into any one investment, however, is the subject of much debate and countless pages written.

Famed investors, from Warren Buffett to Peter Lynch, have all advocated a concentrated portfolio to investors who know how to value businesses. Because stocks are simply little pieces of a businesses and because relatively few business significantly outperform the rest, you have to be concentrated in order to capture the above-average returns. Buffett has gone so far as to state that you only need to own two or three great businesses in a lifetime in order to have a wonderful result.

So given the affinity for concentration among the world’s top investors, why aren’t their holdings concentrated among just two or three stocks? Two or three stock portfolios are exceedingly rare even among the Buffets of the world which, on the surface, appears to be a contradiction. It is with this apparent paradox in mind that we turn to today’s topic, position sizing. Before we do, however, let’s review a few key concepts around portfolio construction.

Portfolio Construction Reviewed

In Episode 60 titled Warren Buffett’s Ground Rules, we discussed the three categories in which Buffett placed his partnership’s investments. The categories are generals, workouts and controls and we will briefly refresh each of them before moving along.

A “general” is a wonderful business purchased at a fair price that can be held for decades. Think Buffett’s purchase of American Express that dates all the way back to his partnership days and which he still holds today. Businesses like this should only be sold if they become egregiously overvalued or if some fundamental aspect of their business is permanently impaired.

A “workout,” is in essence a special situation. It’s a business that you don’t intent to hold for the long term but one in which value can be recognized in the near-term due to some type of catalyst. For us, Garrett Motion has been just such an investment. Purchased out of bankruptcy and slowly improving its capital structure over time, it offers significant upside to investors who are willing to do the work to understand it.

“Controls,” are investments wherein the investor takes control of the company and forces positive change. The investor recognizes uncaptured value in the company, usually the result of poor management, that can be extracted by taking over the company and correcting management’s errors.

In Episode 81 titled The Century Portfolio, we further expound on the topic of portfolio construction by discussing the barbell strategy. Popularized by author Nassim Taleb, the barbell strategy frames portfolio construction through the lens of risk. A barbell portfolio places assets on opposite ends of the risk continuum rather than at its center in the same way that weights are placed at opposite ends of a barbell and not the center. Barbell portfolios hold a majority of assets in as close to zero risk assets as possible and counterbalance those positions with a small percentage of high risk and potentially explosive payoff assets on the opposite end. This leads to a heads-I-win-a-lot-and-tails-I-don’t-lose-much approach to portfolio construction.

Position Sizing

Having now reviewed some of the basics of portfolio construction, let’s turn our attention to the principles that put these concepts into action. We will outline five basic steps below but keep in mind that no “rule” in investing is truly a rule. We can never toss our thinking out the window and blindly follow a system if we want to achieve truly stand-out results. With that in mind here are the basic principles that can act as a guide to capital allocation decisions.

Principle 1

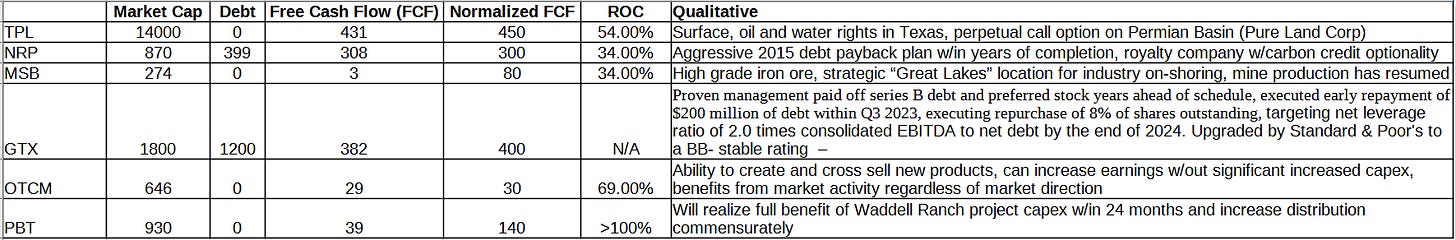

First, rank order your investment ideas based on the three criteria already mentioned which are price, return on capital, and moat. The table below compares six of our highest conviction ideas based on market cap, debt, free cash flow, normalized free cash flow, return on capital, and qualitative factors, or in other words, moat.

Placing your highest conviction ideas side by side and comparing them based on a few simple metrics really helps clarify how well one idea stacks up against another. For example, on a simple market-cap-to-cash-flow basis we can see that Mesabi Trust (MSB) and Natural Resource Partners (NRP) can be purchased for less than four times their normalized cash flow while Texas Pacific Land (TPL) trades at a market cap 32 times higher than its current annual cash flow. Based on this metric alone MSB and NRP are much better investments than TPL.

Because of the capital-light nature of these businesses, they all score well on ROC, except for Garrett Motion (GTX). While GTX throws off significant cash flow, its actual income is anemic to nonexistent meaning that its ROC is also nonexistent. Free cash flow does not account for non-cash charges, while reported income does, meaning that depreciation, interest, and non-cash compensation aren’t included in the free cash flow number. Put simply GTX produces lots of cash but until it reduces its debt load that cash won’t translate into income. Once management completes its debt repayment plan the companies earnings should rise, its credit rating should improve, and it should trade in line with other comparable OEM companies.

On a qualitative basis TPL owns the surface, water, and oil rights to nearly 900k acres of oil rich Texas land and as such represents a perpetual call option on some extremely valuable real estate located in a favorable jurisdiction of the United States. Mesabi Trust by comparison has a single revenue source in the form of iron ore and has a touch and go relationship with its mine operator Cleveland Cliffs. In the near term, earnings could be impacted but over the life of the trust unit holders will eventually be compensated for the value of the property. Finally, NRP still carries nearly $400 mm in debt which is a drain on distributions to shareholders but which management is also keenly aware of and intent on eliminating within the near future. Furthermore, NRP’s income is being diversified across multiple royalty types and, of the stocks represented in the table above, represents the most diversified asset base of the group.

While there is no objectively “best” investment in the group, it’s still important for investors to compare each of their top ideas against all of the others and settle on what they determine to be the best investment. This process clarifies your thinking and forces you to more fully understand your thesis behind each idea.

Principle Two

Second, identify your highest conviction idea and start building up a position. Focus on you single best idea and continue adding to it until something changes. Focusing on your single best idea is what keeps your portfolio concentrated while the next two principles are what diversifies it.

Principle Three

Third, switch the investment that your buying more of as soon as another one replaces it in the number one spot. This could happen for any number of reasons to include your number one idea becoming overvalued, another idea becoming undervalued or because your research leads you to a company that you weren’t previously aware of. In any event, your task is to compare your current holdings against each other and against any new companies you’ve researched such that you always have a number one stock on your buy list.

Principle Four

Fourth, sell any generals that are egregiously overvalued or who’s fundamentals are permanently impaired and sell any workouts or controls who’s thesis has played out. When selling, “sell slowly” is a rule of thumb that often prevents rash decisions. It took well over two decades for my first 100-bagger to play out and there were many times along the way when that general investment appeared overvalued and could have been sold. If in doubt leave the position alone and let compounding interest work its magic.

Principle Five

Fifth, add small asymmetric bets when appropriate. A 1% portfolio position is a rounding error if it fails but can double the value of your holdings if it appreciates 100x. We’re not advocating buying into every half-baked idea with the justification that its only a 1% position, or that it could 100x, but rather encouraging investors to take a small position in legitimate opportunities. If you really understand the idea and believe it is truly an asymmetric opportunity, then add it to one side of your barbell portfolio and forget about it. It will either grow to be a meaningful part of your investment holdings or will go to zero and be forgotten.

The table below demonstrates how an investor following the rules above could begin with the intention of owning a single stock but over a number of years end up with a modestly diversified portfolio. In most cases following these principles would lead an investor toward a portfolio of more than five but less than twenty stocks in total.

Aiming to invest everything in one’s best idea counterbalanced with reluctant selling and shifting conditions in the real world slowly diversifies your holdings but not so much that you end up as a closet indexer. In the table above, the investors ends up with eight total positions which even if equally weighted would amount to a 12.5% concentration in each investment, an amount considered concentrated by most investment advisors.

A 12.5% equal waiting across eight stocks, however, is almost completely impossible given all of the factors that would have influenced the investors original position size and the position’s subsequent performance. In the real world the 8 stock portfolio listed above would have a few positions that dominate the portfolio and a few that represent a rounding error in terms of total position size.

Conclusion

In summary, the investor should not set out to construct a 10x10 or 60/40 portfolio that follows a mechanistic approach to position sizing but rather should aim to invest all of his capital into his best idea. Because changing conditions and new information are always replacing an investor’s current best idea with new ones the total number of holdings slowly creeps up over time. At the same time old positions fall out of the portfolio, generals in secular decline are sold, as are workouts and controls who’s thesis has played out, and in other cases an investment simply eliminates itself by going to zero.

This principled method geared at always allocating to your best idea not only diversifies your holdings but it allows your best investments to grow in size without being mechanistically sold off. Despite our best efforts to outsmart the market many of our favorite ideas could prove to be mediocre investments. It could be that a single 1% asymmetric bet left to its own devices would come to dominate an otherwise average collection of investments. This single bet could drive the returns of the entire group such that the portfolio still outperforms the market even though the outperformance came from a single investment. Or a totally different set of circumstances could play out. The point is that a principled approach to concentration should produce adequate diversification over time, allow your best investments to run, and allow ample opportunity to outperform the standard indexing approach.

With that we wrap up Episode 101 of the show. We appreciate all your support and love hearing form the audience. We also enjoy when you guys show your support with a Boost on the Fountain app. We look forward to bringing you another actionable investment idea next week.